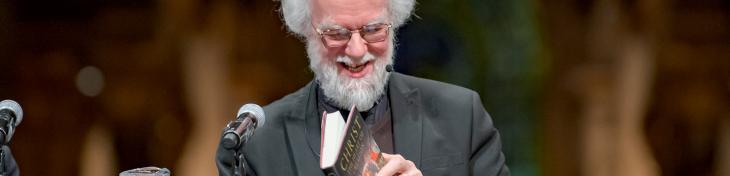

Mirrors of the Light: Contemplating Icons

Mirrors of the Light: Contemplating Icons

Charlotte Gibson reflects on contemporary and ancient icons, and their place in our faith today.

1. Layers of Light

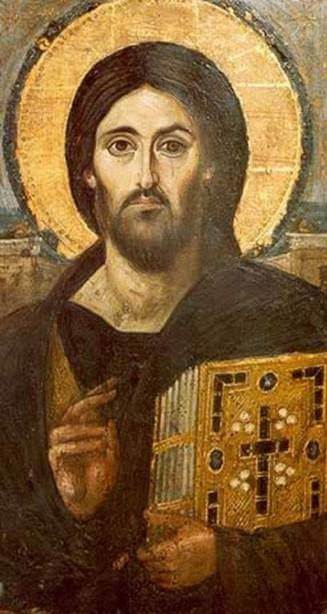

Christ Pantocrator - Icon in the Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai.

Coming from a reformed, Methodist background, I never imagined that I would find myself painting icons. There is an ongoing debate about whether one writes or paints an icon. For simplicity, I say paint because both the Russian and Greek words can mean both write and paint.

However what I have found over the last few years is that God uses them to speak to us in many ways. The processes involved in traditional iconography are often slow and frustrating for someone who is keen to rush on to the next thing.

From preparing the board (which is coated with a mix of rabbit skin glue and chalk, called gesso), to adhering the gold leaf (which is adhered over layers of shellac or clay bole, each sanded to perfection), to allowing each layer of paint to dry (made of egg yolk, vinegar and mineral powders), an icon can take weeks to even start painting. But those very processes allow space for the Holy Spirit to whisper words of encouragement and clarity, as each layer of light brings to life the face of the saint being depicted.

In these short reflections over the next month I want to help you to engage with icons at the pace at which the Spirit encourages us to go.

The first one we’ll look at is Christ Pantocrator, a 6th century icon found in St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai. This is Christ ruling over the universe, with a decorated book of the Gospels in his arm as he gives a blessing.

Immediately the gaze is drawn to Christ’s face, which frankly looks a little odd. I encourage you to look at his face for a while, and then cover one side and gaze a while, and then switch. What do you notice? You may notice that one side of the face looks more serious, or one side looks kinder. What do you learn about Jesus in doing this?

Finally, look at the gold nimbus around Christ’s head. Gold represents the uncreated divine light of God surrounding the subject of the icon, as the saints are considered mirrors to this light. Do you feel surrounded by the warmth of God’s light when gazing at this image?

2. Reflecting the Divine Light

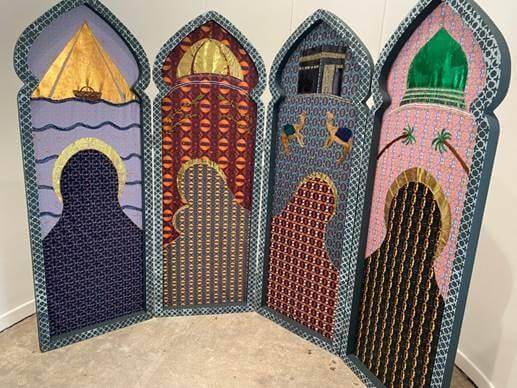

From Farwa Moledina’s ‘Women of Paradise’ exhibition. Photograph by the author.

As a Christian iconographer, I find religious art of other faiths fascinating. I recently had the privilege of visiting Farwa Moledina’s exhibition ‘Women of Paradise’ in the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. I took with me members of the Women’s Theology Groups that I run and we had a profound time just looking at these fabric panels, depicting a sense of four righteous women in Islam.

The first two panels were particularly interesting, as the first depicts Aasiyah, the adoptive mother of the man we may know as Moses in The Book of Exodus. The second depicts Maryam, or Mary, Mother of God or Godbearer, as is her title in Christian iconography, indicated by the abbreviated letters ΜΡ ΘΥ in the corners of icons of her.

In Islam, it is not permitted to draw or paint prophets or righteous people in Islamic history, because it is believed that it risks idolatry. What Farwa has so expertly done here, using the medium of fabric, is to give us the sense of the characters, without details that might carry this risk.

And yet, my eyes fill in the image of Mary in the second panel, because that shape of her cradling Jesus is so familiar. In these images we see the women of Islam take their place in their faith in a modest way – even the nimbuses are modest in size, yet they still reflect the gold divine light of God.

While the final two panels (Khadijah and Fatima, wife and daughter of Muhammed) depict women only found in Islam, there is a sense of solidarity in this piece – particularly, as I found, for women of faith. Sometimes, as women in contemporary society, we can fade into the background, busying ourselves with the necessary tasks at hand. Yet we are not invisible: God’s light persists around us so that our mark on this world is made through the carefully embroidered silhouettes of our lives contrasting against it.

Find out more about the Women of Paradise exhibition.

3. Windows to Heaven

My favourite icons are those that, as you look at them, seem to look right back at you.

When I am painting an icon, it is the eyes that I often find myself obsessing over, trying to get them just right, trying to make sure that I can feel them looking at me. The reason for this is because traditionally icons are considered to be windows to heaven. Whether you take that literally or not is a matter of your own theology and understanding, but increasingly, as I sit at my desk facing a wall of icons and feel the eyes of the saints upon me, I have a more tangible sense of God seeing into my life.

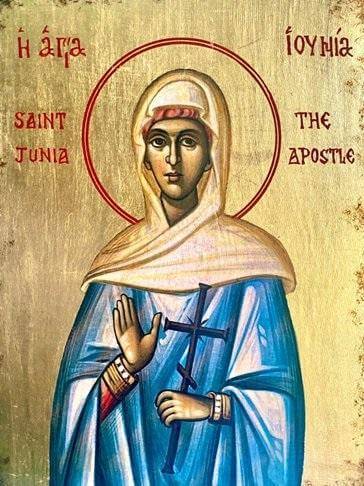

The icon I wanted to help you look at today is an icon of St Junia. Very little is known about her, apart from St Paul’s mentioning of her: “Greet Andronicus and Junia, my fellow Israelites who were in prison with me; they are prominent among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was.” (Romans 16:7, NRSVUE). There has been a debate about whether Junia was a woman or not since she is named in terms of apostleship, but since her name is female and she is mentioned alongside other couples, contemporary scholarship points to her as a woman.

As a woman priest, her gaze upon me speaks to me of her solidarity, of her patience in being recognised for who she is and therefore of the women priests who went before me. But icons are for the whole body of Christ, not just the clergy, and not just for women. What do you see as you look in her eyes? What do you feel as her eyes meet yours while surrounded by that gold uncreated light of God?

4. An Icon of Solidarity

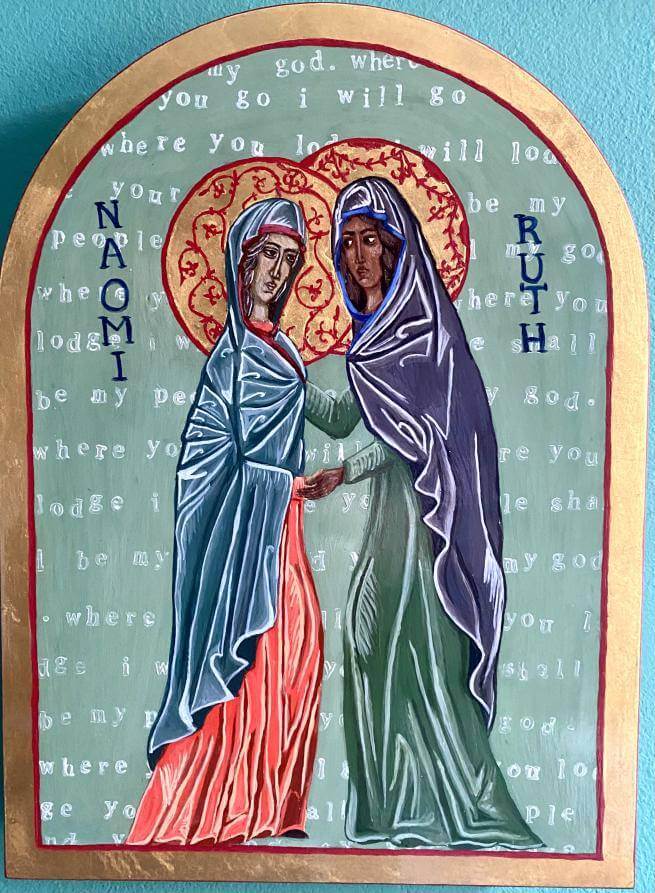

Last week we reflected on the importance of the eyes of the saints in icons. The person praying with the icon feels the gaze of the saints. In this last reflection I want to offer you one of my own icons in which the saints look at each other instead, and which I painted while on retreat preparing to being ordained.

In this icon, Ruth and Naomi gaze upon each other. Their story has been told and retold in many contexts, but I wanted to paint them in the context of their solidarity with each other.

The book of Ruth in the Old Testament tells their story: both are left without husbands or children to take care of them, they stay together in order to survive in a world which was not built for women. I was ordained alongside eight other women, so this felt like a good story upon which to reflect as we prepared together for such a big responsibility and adventure.

I grew up in a church which emphasised the importance of the Bible (and would never pray with icons or have them in church), therefore my starting point for most of my icons is the Bible. The first thing I do is find a verse, and then I paint it on the icon using egg tempera paint and stamps. Only then do I paint the images of the saints on top. This grounds me in all the traditions that have formed me, and helps those for whom iconography is unfamiliar to find a starting point for looking at the icon. It also gives a voice to those represented, so that those looking at it can hear the saints as well as see them.

I leave you with this image, and encourage you to spend some time looking at it, maybe read the book of Ruth and then look at it again. See what you notice in the shapes, look at their eyes, their hands and the Bible verse behind them. What does God want you to hear today?