Sacred Remnants: a journey through objects and faith

Sacred Remnants: a journey through objects and faith

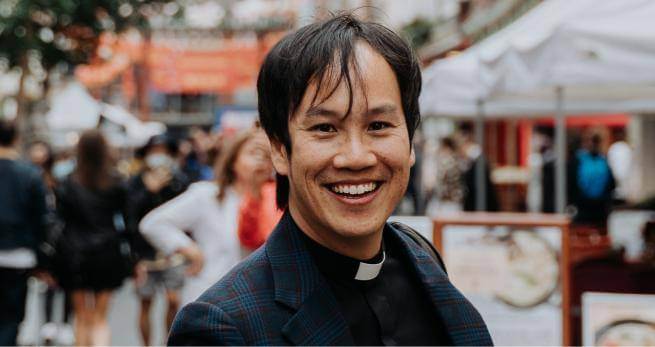

Mark Nam reflects on the everyday objects that intersect with his faith and his heritage to connect him to God in unexpected ways.

Faith is rarely an abstract thing. It lives in the folds of daily life, in the objects we hold, the meals we share, and the stories we inherit. As a third-generation British-born Chinese Anglican priest, I often find my faith entangled with my heritage—sometimes in ways that surprise me. This series of reflections explores that intersection through everyday objects that have shaped my life. They are more than just things; they are bearers of memory and meaning. They connect me to my ancestors, to a sense of home, and, in unexpected ways, to God.

1. The Name Chop: Identity and Ink

When I was young, my parents gave me a name chop—a small, weighty seal carved with Chinese characters. Made of jade, square, and cold to the touch, yet it felt alive in my hands. It carried an authority beyond its size, for with one press into cinnabar ink, it imprinted my name in red script older than my understanding.

That name chop meant more to me than just an elegant flourish on letters or artwork. It was a link to something deeper. Our family name had been lost when my grandfather arrived in the U.K. in 1918. Like many Chinese immigrants, he introduced himself in the traditional way: surname first, given name last. The British immigration officers, unfamiliar with the custom, mistook his given name for his family name. And so, by a clerical accident, our lineage was rewritten. Ever since, we have been known as the Nams—carrying a name that was never meant to be ours.

But the name chop whispered a different truth. It reminded me that our history was not erased, only misfiled. It stamped in blood-red ink the reality of who I was, even when the records said otherwise.

Names matter in Scripture. Time and again, God renames His people to reflect their true identity: Abram becomes Abraham, Sarai becomes Sarah, Simon becomes Peter, Saul becomes Paul. A name is not just a label; it is a calling, a belonging, a covenant. And yet, names can also be lost, stolen, or rewritten by forces beyond our control. The Israelites wept by the rivers of Babylon, called by foreign names, their heritage seemingly erased. And yet, God never forgot them.

The name chop my parents gave me is a small sacrament of that truth. Even when human hands miswrite our stories, God remembers who we are. He knows our real names. In Christ, we are given a name that cannot be taken away: Beloved.

2. Chopsticks: Two Sticks, One Love

When I was a child, I avoided using chopsticks in public. At school, I would sometimes refuse to eat the food my mother had prepared, hiding from the unspoken but palpable message that being Chinese was something to be embarrassed about. Chopsticks, with their quiet defiance of forks and knives, felt like a symbol of otherness I wasn’t sure I wanted to claim. So I pushed them aside, preferring the anonymity of Western cutlery.

And yet, at home, chopsticks were love.

Mealtimes in a Chinese household are rarely about the individual; they are communal, a choreography of sharing. At the centre of the table, dishes are laid out, not in isolated portions but in abundance, meant for everyone. And in that quiet act of care, my parents would lift the juiciest, most tender morsels from the middle of the dish and place them into my rice bowl with their own chopsticks. They didn’t need words to say, I love you—but love was there, in the silent offering of food, in the attentiveness of knowing what I liked best, and in the unspoken assurance that I was seen and provided for.

Chopsticks, I have come to realise, are deeply theological. They are instruments of grace, never meant to serve just oneself but always extending towards another. They resist the loneliness of individual plates and instead assume a world where generosity is the default posture. Love, after all, is not a possession but a movement—a reaching towards, a giving, a sustaining.

In the Kingdom of God, perhaps we are all meant to be like chopsticks: simple, unassuming, always working in partnership, always lifting, always offering the best to another. And perhaps, in those small, everyday gestures of love, the divine is most profoundly revealed.

3. The Slipper: Stepping Beyond the Threshold

Several months after my mother died, my father and I decided to rearrange the beds. It was one of those quiet, necessary tasks that grief brings—something to do with your hands when your heart feels too full. As we lifted the mattress and shifted the frame, we found her slipper—velvet to the touch, slightly misshapen, wedged between wall and floor.

It is strange, in some ways, to cry over a slipper. But that’s what we did. My father picked it up, held it to his face, and I did the same. We wept—not just for her absence, but for the sudden nearness of her. That slipper had once been part of her daily life, and now it had become a remnant of her presence, quietly waiting to be found.

I remembered how she used to wave it at me when I was deliberately disobedient. It was never used, not really. It was a warning, yes—but one bound up in familiarity and love. Authority softened by affection. A kind of unspoken understanding between us.

In Chinese culture, you take off your shoes when entering someone’s home. It’s an act of respect, a way of honouring space and presence. Somehow that made sense to me in that moment—her slipper was still there, but she had stepped beyond the threshold.

It reminded me that so much of what holds a family together is built from the ordinary: the quiet routines, the gestures that repeat until they become part of who we are. This slipper, for all its simplicity, had carried something of that weight.

Jesus often used everyday objects to speak of the holy: a coin, a loaf of bread, a cup of water. Things easily missed unless you were paying attention. Faith, I’ve learned, isn’t always found in the spectacular, but in the worn and familiar. The things we pass by. Or stumble upon. Or hold to our faces when words fail.

The slipper now rests in a drawer I rarely open. But I carry its memory—the velvet feel, the tears it drew, the glimpse of something sacred in something so small.

4. A Folding Screen: Framed by Love

In the corner of my study stands a full-sized Chinese folding screen, its lacquered surface adorned with golden birds on delicate branches. It was given to me by my father shortly before he died. My mother had already passed away when I was in university, and so this screen has become more than just a piece of furniture—it is a silent witness to memory, a presence that holds the shape of absence.

The screen is a curious thing. It both divides and connects, conceals and reveals. In grand Chinese homes, such screens were placed not merely for decoration but to shape space—to soften harsh angles, to create harmony. My screen does something similar for me. It does not block off, but it frames. It offers a way of seeing, of remembering, of holding together the fragments of family, heritage, and faith.

The birds on the screen remind me of Jesus’ words: Not one of them falls to the ground outside your Father’s care. In Chinese art, birds often symbolize freedom, migration, and continuity across generations. There are cranes, swallows, magpies—each with their own meanings. When I look at the screen, I see more than its craftsmanship—I see the hands that gave it to me. My father’s, marked with time and love. My mother’s absence, somehow present in the space it holds.

There are moments when grief still moves like a shadow across the panels. But then the light shifts, and I remember: this screen does not close off the past. It makes space for it. It reminds me that love, like faith, is not lost—it is folded into the shape of our lives, shaping us still. It stands, quietly, offering shelter to all the stories I carry.

5. The Teapot: Poured Out in Love

In the cupboard of my home sits a blue-and-white calico teapot set, brought out only on special occasions. At first glance, it looks Chinese—the delicate floral pattern curling like brushstrokes on porcelain. But it is English pottery, solid and quietly elegant. My parents began collecting it after they married, buying just one piece a year. A cup one anniversary, a saucer the next. With patience and devotion, they slowly built a full set.

As a child, I barely noticed it. It was the “good china,” tucked away for guests or special occasions. But now, with both of my parents gone, my wife and I lay it out with care for our own children. On birthdays, feast days, or afternoons when we want to remember, we gather around it. We warm the pot, fill the cups, and sit together. At first the tea is hot, the steam rising, and conversation comes easily. But as the tea cools, so too does the room. Voices soften. Silence becomes more comfortable. Something holy begins to settle in.

There is a kind of theology in tea. It resists haste. It draws people together without performance or pressure. It teaches us how to tend and to wait, how to receive and to give. Tea is a blend—of soil and leaf, heat and water, strength and gentleness. It is also a reflection of who I am: British-born Chinese, living between cultures that have not always known how to speak to one another. But tea has taught me that we are not meant to live in halves. Wholeness comes when we are steeped fully in who we are—our history, our longing, our heritage—and offered with love.

Yet even this treasured set, lovingly collected over a lifetime, is not the truest vessel. That place belongs to another cup—the one Christ offers at his table. The cup of grace, of covenant, of a love poured out and never withheld.

This teapot set, with all its beauty and memory, points beyond itself. It gestures toward the table where all our stories—our fragments, our losses, our hopes—are gathered and made whole in him.

So may you lift your own cup with intention. May you taste the warmth of memory, the gentleness of presence, and the fullness of a love that still invites us—all of us—to drink deeply and be satisfied.