A Pastoral Pope amidst God's People

A Pastoral Pope amidst God's People

Anna Rowlands reflects on Pope Francis' papacy.

Pope Francis has died at the age of 88, leaving behind a Church that whilst aware of his slow and painful diminishment over the course of the last two years, has nonetheless experienced the shock of his sudden and mercifully peaceful death early on Easter Monday morning. In a symmetry quasi cinematic and seemingly providential, his pontificate began twelve years ago among the crowds of St Peter’s Square, reversing the usual papal protocol with his head bowed to receive the blessing of the people, and it ended hours after being driven through that same square to be amongst the applauding Easter pilgrims. Amongst the crowd celebrating the Resurrection is surely where he would have wished to be in his final hours.

Francis made the lives of ordinary people – believers and non-believers – his central focus. He did this not because he was a ‘nice’ person (like any of us, he wasn’t always ‘nice’), but because he believed profoundly that the way of Jesus Christ is to live a life for and with others. This involves, like the Good Samaritan (who stands for Christ), being willing to be moved in one’s very guts by the pain and joy of my neighbour and to accompany each other. That neighbour is both anyone that I happen to encounter concretely and is, in theory, any person regardless of their markers of identity. We are all human first, and every living person is my kin. We live with kinship within kinship, as siblings of a common creator and within a creation in which all – and everyone – is gift, incredible though that might seem.

His prophetic model of a ‘localised universalism’ – love for this person here in the name of the love that embraces all persons - challenged the narrow, or as he expressed it, ‘narcissistic’ populisms of our time. Francis turned out to have a remarkable ability to diagnose the meta-trends of our time that are traced in the lives of real people. He called us to heal through the search for justice and peace those wounded by scourges of poverty, climate injustice, migratory displacements, wars, unemployment and homelessness. He was a tireless advocate for those with disabilities, the elderly and all discarded life. His simple call for land, labour (work), and lodging (housing) for all resonated globally, especially with the world’s poorest and least heard. It was their voices heard through his teaching that he cared most about raising up. It was these people he wanted to draw close to in gesture and word. Whether they saw themselves and recognised their cries in his social encyclicals mattered more than whether a politician found them palatable. Having failed once in his life in the face of political power, as Pope he became fearless in speaking truth to it.

Yet his core service to the world was through his shepherding of the Church. In a deeply pastoral papacy, it was the dignity, faith, fragility, promise and difficulty of the lives of ordinary believers that he sought to attend to, unflinchingly, as a pastor. Unafraid of the messiness, complexity and tensions of life he sought to bring a message of joy, mercy and hope as the necessary Christian dispositions and practices that would transform lives. He knew this ‘from the inside’, confronting his own weaknesses and deeply aware of himself as a sinner dependant on God’s grace. His papacy seemed to be formed around a discernment of the mysterious capacity of the Jesus to reveal the truth to those whom he encountered always with the face of mercy, to hold truth and love in indivisible relation. It is unsurprising, then, that so many saw in him something of Jesus – including those who do not otherwise have much time for the Church institutional.

Perhaps most telling in these early days of mourning are the words of the parish in Gaza who he phoned most evenings over the last months. “We are orphans now”, they said. The paternal care which Francis offered was felt most amongst those who most clearly suffer the ravages and exposures of our modern age, whose vulnerabilities have been manufactured by the various forces of market, weapons, borders and climate change, yet also most those who have felt most excluded or peripheral to the Church itself.

The movement of this papacy, if one can think in such terms, was, I think a ‘descending’ one. A pope who lowered his head to request the blessing of the crowd, he sought to show a way towards entering ever more deeply into the mystery of our own broken, fragile, failing yet redeemed and graced humanity. He sought to bring the papacy down from its pedestal, living in Santa Marta, reforming even to the last the trappings of papal privilege. He will fittingly be buried in a simple coffin, laid in the earth, with a simple inscription: Franciscus. To the last his gestures as much as his words invite us to a life, simpler, gentler, kinder, closer to suffering and unafraid of the civilisational power (not weakness) of compassion, empathy, mercy and love as the pathway to truth. It was a descending movement that sought, in Christ, to raise us up.

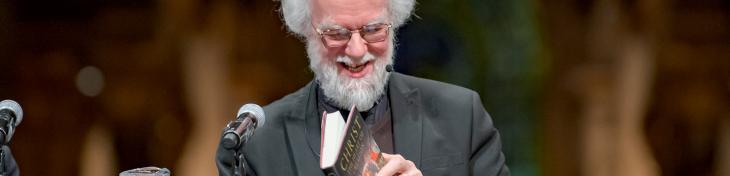

Header Image: © Mazur/catholicnews.org.uk https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/