Words which changed the world

Words which changed the world

James Roberts explores the life and legacy of William Tyndale.

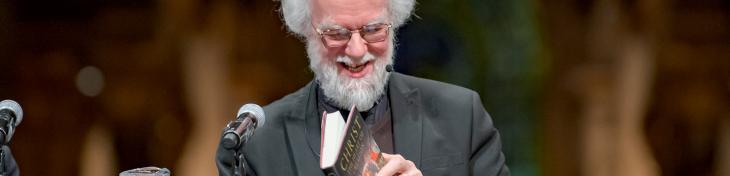

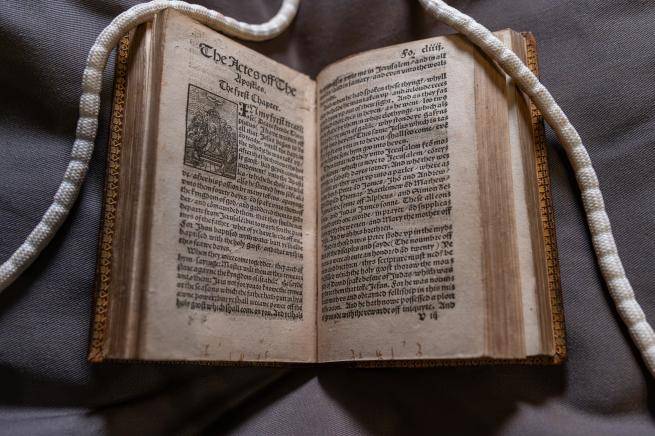

1. William Tyndale's New Testament

500 years ago, a Priest named William Tyndale published an English translation of the New Testament. This project may seem unremarkable to us in 2026 when we are so accustomed to reading Scripture in our own native language. But to publish a portion of the Bible for mass consumption in 1526 was a revolutionary act; one which changed not only the course of Christianity in England, but the culture of the nation, and even the English language itself.

St Paul’s Cathedral is home to a first edition of Tyndale’s New Testament, one of only three remaining in the world. It is unassuming in appearance. Yet, unearthing the story behind this little book reveals the ground-breaking nature of Tyndale’s work and theology.

In Tyndale’s time, the Bible was read in Latin. As many people could not read or understand Latin, their engagement with Scripture needed to be mediated – a Priest would interpret the text for a congregation, according to the authorised teaching of the Church.

William Tyndale, in contrast, passionately believed that all people should have direct access to the Bible in their native language and the freedom to interpret its meaning for themselves. Therefore, he embarked on a project to translate the Bible into English.

Tyndale's work was condemned, however, by the Bishop of London and he was forbidden from proceeding. Inspired to push ahead with the translation and get the Bible into the hands of the people, Tyndale had to travel to Germany – the centre of the Protestant Reformation – to start printing. He was betrayed and had to continue his secret work in Worms. It was from here that he smuggled his translations back into England.

However, the authorities eventually caught up with Tyndale, and he was executed near Brussels, Belgium, in 1536.

The story behind Tyndale’s New Testament is one of conflict, of reform, and a radical new vision for how people engage with Scripture. This anniversary year gives us the opportunity to reflect on the dangerous history which is wrapped up with the task of translating the Bible, challenging the familiarity of the Bible in English for us in 2026, and highlighting the extraordinary life and legacy of William Tyndale who lost his life for his convictions.

2. Grounded in the Word

This year at St Paul’s Cathedral we are exploring the life and legacy of the remarkable figure, William Tyndale, who published his English translation of the New Testament 500 years ago in 1526 (one of which is housed in our library).

In order to publish his New Testament, Tyndale defied the orders not only of his Bishop, but also of the Church, and even the King. It is hard to imagine the scale of the risk involved with pursuing this project. Yet Tyndale did continue, resulting in being branded as the ‘most dangerous man in England’ and eventually in his execution. So, why was Tyndale so passionate about translating the Bible into English, and what gave him the motivation and strength to face such daunting and dangerous opposition?

The answer to this question lies in Tyndale’s theology.

For Tyndale, the Bible forms the basis of everything we know about God. A person’s understanding about who God is doesn’t come from our own minds or creativity, but through God’s revelation. Tyndale writes that, ‘God is not man’s imagination, but that only which he saith of himself…God is but his word: as Christ saith’. For Tyndale, this means that everything we know and understand about who God is can only be found through listening to what God tells us about Himself in Scripture.

But a problem arises here for Christianity in Tyndale’s age. If our understanding of God is rooted in Scripture, then how can people learn about God if they can’t understand the language in which Scripture is written? Translating the Bible into everyday English means that people can have first-hand access to understanding who God is, and this forms the foundation of their personal faith.

This introduces a radical equality into Tyndale’s theology. He believed that each individual person has the capacity to navigate their relationship with God for themselves, without any mediation from the hierarchies of the Church. The prayer of the cobbler, he writes, is just as good as the prayer of a cardinal, and ‘…a blessing of a baker that knoweth the truth, is as good as the blessing of our most holy father the Pope.’

Tyndale’s theology is rooted in a belief that everything is grounded in the words of Scripture. And all people, whatever their background, whoever they are, should have access to understanding who God is for them. It was for this belief that he risked everything and lost his life.

3. Words on Fire

500 years ago, in the grounds of Old St Paul’s, hundreds of copies of Tyndale’s New Testament were thrown into a fire. The Bibles burned in the shadow of the Cathedral. And they were destroyed, somewhat surprisingly, by the orders of the Bishop of London.

Tyndale’s translation was perceived as so dangerous to the stability of the Church, that Bishop Tunstall bought as many copies as possible with the explicit aim of destroying them.

This wasn’t just because Tyndale had persevered with translating the New Testament and directly disobeyed the orders of Bishop Tunstall (although this was a significant issue). It was also because of the way in which Tyndale had translated Scripture.

Tyndale was deeply influenced by the theology of the Reformation and the new ways of thinking which were sweeping across Europe. He was especially inspired by the writings of Martin Luther.

The Church, Tyndale believed, had moved too far away from Scripture in what it practiced and preached. The sacraments, for example, should be seen as pointing to the truth of Scripture. And the most important thing was a person’s faith, not the effectiveness of the ritual in which they were participating (‘The promise which the sacrament preacheth justifieth only’, he writes).

So, when he was translating the New Testament, Tyndale deliberately chose words which challenged the practice and theology of the Church. He uses the word ‘repentance’ rather than the traditional term ‘penance’. Whilst this sounds like a minor change, it challenged an entire theology, tradition and system of penitential practice which took root in the medieval period, including the practice of indulgences. He changed ‘church’ to ‘congregation’, and ‘priest’ to ‘elder’, so that the hierarchies of the Church were also put into question.

Tyndale was not just translating Scripture into the vernacular. He was also making theological statements and challenging the very nature of the Church.

The flames which swallowed up Tyndale’s translation 500 years ago show us the ferocious response which his theology inspired. But they also, perhaps more subtly, show us the power which is wrapped up in the nuances of language. They show us that the slightest change of interpretation or translation can have a revolutionary effect, challenging the stability of tradition, unsettling power, and unlocking the kind of change which, like fire, cannot be contained for long.

4. Words of Comfort

William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament was condemned and burned in the shadow of Old St Paul’s. But this act did not extinguish the impact of his work, or his enduring legacy today.

Tyndale had a remarkable impact on the development of the English language. Although his translations were condemned in his lifetime, the tide swiftly changed following his death. As translation of scripture became not only tolerated but celebrated in the years which followed, Tyndale’s work became foundational to future editions of the Bible. The King James Version (arguably the most famous English translation) is highly indebted to Tyndale. In fact, it’s estimated that around 80% of the King James Version comes from Tyndale. If we consider the impact of the King James Version on the English language – not only in England, but throughout the world – then we can trace the profound impact of Tyndale’s work well beyond his edition of the New Testament in 1526.

Tyndale’s linguistic impact is not just a legacy for religious or theological language. He coined phrases which have entered our everyday language to this day; phrases such as ‘from strength to strength’, ‘see the writing on the wall’, ‘fight the good fight’, ‘salt of the earth’ and ‘eat, drink and be merry’. And Tyndale’s prose is beautiful to read too. It has a certain simplicity to it, with short sentences and uncomplicated vocabulary, yet it is underpinned by a masterful sense of rhythm and pace.

However, I have a feeling that Tyndale himself wouldn’t be very concerned about this part of his legacy.

Tyndale’s lasting impact (which I’m sure he would be proud of) is the accessibility of the Bible in people’s native languages today.

The refrain which repeats throughout his writing is his desire to make Scripture accessible to everyone. This wasn’t just for the public’s general interest. Rather, it was to allow his readers to have a direct relationship with God. Scripture was a reminder of God’s presence with all people, and Tyndale wanted to empower people with the comfort of this promise: ‘Therefore let us arm our souls with the comfort of the scriptures. How that God is ever ready at hand in time of need to help us,’ he writes. As someone who faced extreme persecution, the words of scripture were his source of strength and truth in the face of trouble and danger.

As we reflect on Tyndale’s legacy, 500 years since he dared to publish the New Testament, we might ask ourselves which words we hold to, where our comfort comes from, and which beliefs we are willing to risk everything for in order to defend them.