Explore Christian life and faith

Explore Christian life and faith

Learn about Christian spirituality, faith and social justice at events at the Cathedral and online, as well as through our unique resource library containing films, podcasts and more.

You’ll find leading theologians, scholars, speakers and writers exploring everything from deepening understanding of the Bible, learning how to pray, to how Christianity changes our everyday lives.

For those looking to make a difference in their community, our faith in action resources provide guidance for Christians looking to take action on climate change, racial justice and young people’s mental health.

Events on spirituality and social justice

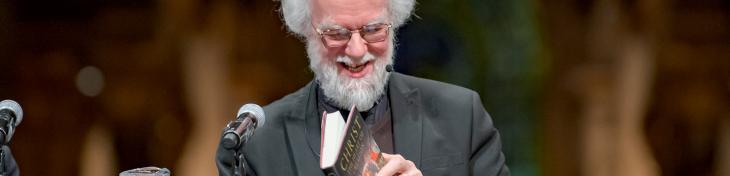

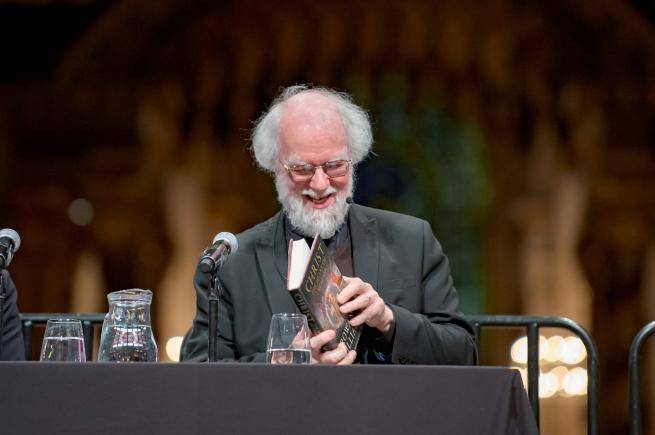

St Paul’s Cathedral runs a year-round social justice and Christian spirituality programme. Our events draw a diverse crowd of attendees, and have featured prominent theologians and speakers, including Rowan Williams, Paula Gooder, Michael Curry and David Suchet.

Find out about events to come to – in person and online – to learn more about the Christian faith, spiritual life and social justice.

Films, reflections and more

Explore Christian spirituality, faith and social justice with our unique library of films, podcasts, panel discussions and specially-commissioned reflections.

Find films, podcasts and written reflections exploring a huge range of subjects – from Rowan Williams’ talk ‘Jesus Christ: The Unanswered Questions' to 'A Spirituality of the Body’ to David Suchet’s mesmerising reading of the whole of the Gospel According to Mark.

Featured films

Rowan Williams answers the question 'Who is Jesus for you?'

At the event 'Jesus Christ: The Unanswered Questions' in St Paul's Cathedral, Rowan Williams is asked 'Who is Jesus for you? and this is his answer.

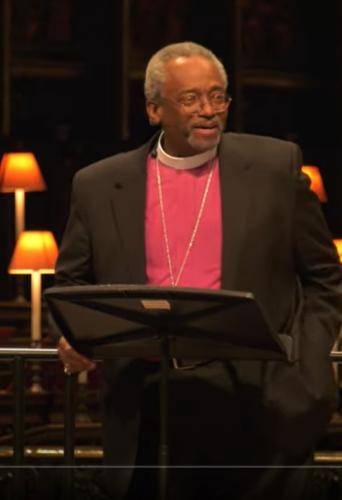

Where Love Is The Way: The Jesus Movement Now

Bishop Michael Curry talks about why he is a follower of the Jesus Movement and how love can change the world.

The Gospel According to Mark read by David Suchet

David Suchet’s dramatic reading of the whole of Mark’s Gospel, recorded live in St Paul’s Cathedral.

My Soul Glorifies the Lord: Jesus' female disciples

Two Professors of the Early Church explore Jesus’, Paul’s and the early church’s attitude to women’s ministry and discipleship and say the evidence shows that women were integral to Jesus’ mission, Paul was positive about women’s ministry, and the early church was far more inclusive and radical than we thought.

Lower than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity

Diarmaid MacCulloch tells a 3,000-year-long tale of Christians encountering sex, gender and family, from the Bible to the present day.

In Green Pastures: The Psalms in Prayer and Music

Paula Gooder introduces some of her favourite psalms and their themes of joy, lament, comfort and reconciliation, and reflects on how they can draw us closer to God. With live music from members of the St Paul’s Cathedral Consort performing settings of psalms from across the centuries and readings by Adjoa Andoh, actor and Licenced Lay Minister in the Church of England.

Take action

Our newsletter

Sign up to our adult learning newsletter and receive weekly reflections by email as well as updates on our newest resources and upcoming talks and events.